04 Apr Panama hat – an Ecuadorian tale

The origin of the hat and its history

The Panama hat is the famous wide-brimmed hat, made of very light straw, that has become in the modern common imagination a symbol of elegance, success and style, but its history is very ancient. First of all, we must immediately clear the field of any misconception: although from the name one is led to think that the hat was originally produced in the Central American state of Panamà, in reality this headgear is known in most of Latin America as ‘sombrero jibijaba or montecristi’, namely the two Ecuadorian (!) towns, located in the province of Manabì, where it was originally designed and produced.

If we want to go even further back in time, we would have to account for the fact that the first people to use this kind of hat were the aboriginal peoples of the Ecuadorian coast; they too must had already appreciated the practicality and comfort of the toquilla straw, from which the hat is made, and its good protection from sun and rain. It is said that the Spanish colonists were inspired by these indigenous headgears in order to get to the final idea and prototype of what would become one of the most popular hats in the world.

As early as the 19th century, the Panamà gained prestige and the first to receive one as a gift was Napoleon Bonaparte himself, courtesy of the King of Spain. In 1830, Ecuadorian artisans managed to obtain a promise from the state that the toquilla straw would not be sold abroad, thus keeping the production within the country; to this end, a handicraft school was set up in the city of Cuenca, in the southern part of Ecuador, where we first discovered this interesting story while we were staying there a few years ago during our trip.

In 1849, almost 200,000 Panamá hats were exported abroad for sale to the general public and a few years later the hat was presented at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, at the time one of the most important showcases for displaying the latest technological, scientific and cultural developments. From then on, the hat gained international recognition, so much that by the turn of the 20th century, almost 50,000 hats were distributed to American soldiers on assignment in the Philippines or the Caribbean. And it was in the United States of America, to which most of the exports from Central and South America came, that the Panama hat caught on, becoming synonymous with elegance and success; the first specimens were worn by workers who had worked on the Panamanian isthmus (1900-1914), hence the misunderstanding about its real provenience.

Once it entered American culture, of course, the Panama got its universal consecration with the cinema and the various celebrities who wore it regularly: Humphrey Bogart, Frank Sinatra, Winston Churchill, Al Capone and many others helped this fashion catch on (a model called ‘El Capone’ still exists today!). In 1946, almost 5 million hats were exported worldwide and even today, thousands and thousands of dollars are spent to get one of the most prized examples.

Perhaps one of the most curious things is the fact that while in Ecuador the hat continued to be worn traditionally by peasants and the more modest sections of the population, in the rest of the world it slowly became a status symbol of the wealthier classes. These are the paradoxes of history from which the events do not always follow a logical and causal order, but instead are produced from the chaos and unpredictability of the circumstances.

The making process

Having said this, the Panama hat is the symbol of a unique and highly developed hat-making art.

The toquilla straw is derived from the shoots of the carloludovicana palm, named after Charles IV and his wife Marie-Louise, the first to initiate the botanical cataloging of this plant in America. This particular type of palm grows throughout Ecuador, but only in the Manabí region does it find favorable conditions for growing in abundance and up to a height of 6 meters. Other South American countries have tried in vain to cultivate it in order to produce hats that could compete with the Ecuadorian ones but they have never succeeded.

The leaves of its shoots must be boiled and dried twice before they become extremely tough. The process is complex: the leaves are tied into bundles, then boiled and finally laid out to dry for three days; the darker ones are lightened with sulfur. As they dry, the leaves are thinned and rolled up to form the round threads that will then be woven.

The weaving is very complicated and the best weavers work exclusively in the evening and early morning, before their fingers start to sweat from the heat. The types of weaves are varied, ranging from a broad crocheted lace-like weave to a narrower one called ‘brisa’, which characterizes high-quality Panama hats.

Hats are then classified according to the weave and generally fall into four basic categories: standard, superior, fine and superfine. Looking at a superfino against the light, no ray of light should be seen passing through the hat.

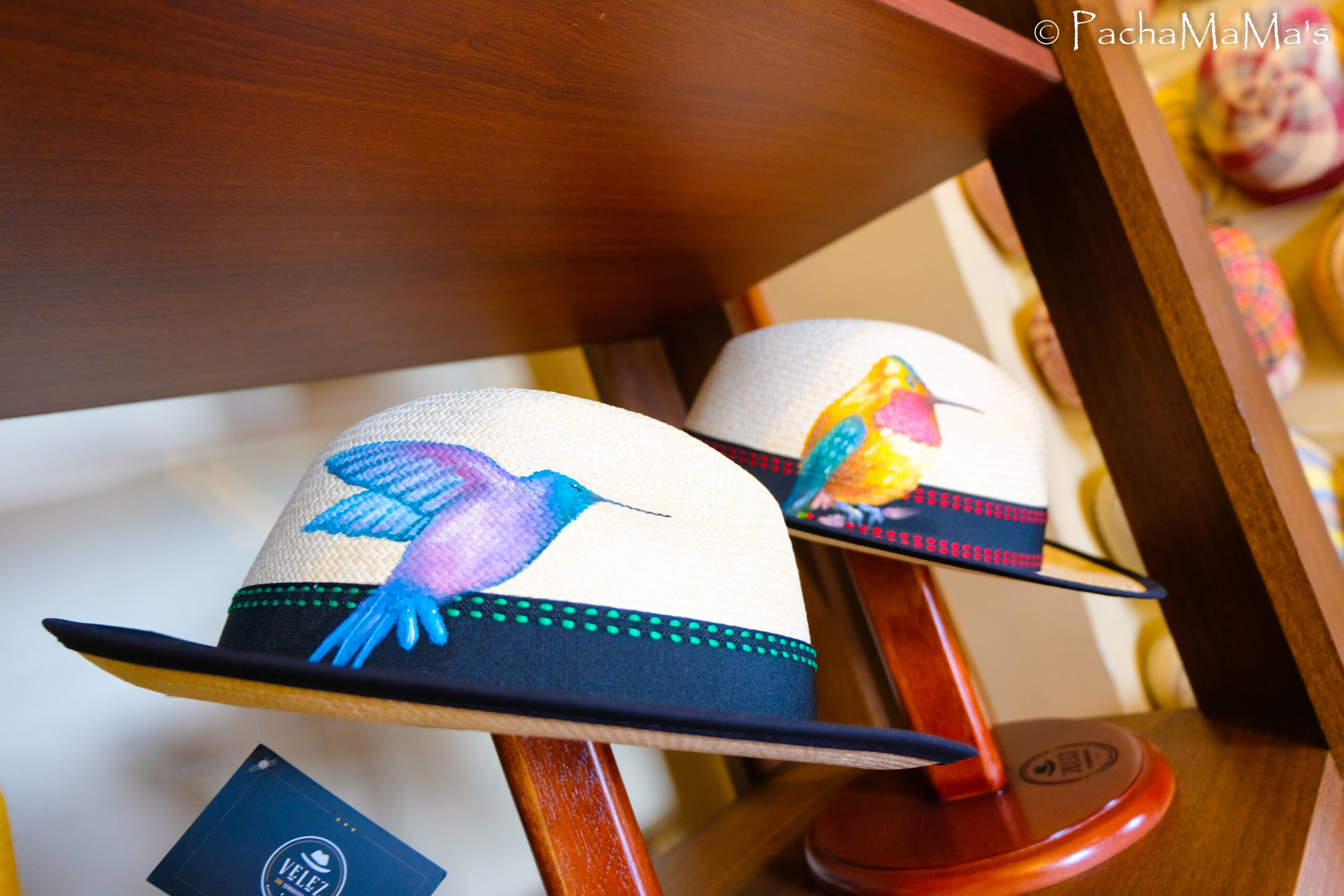

After weaving, the hats are finished, bleached or painted and finally adorned with a ribbon. The sale of hats can start from as little as $15 and reach, as mentioned, extraordinary figures of even thousands of dollars when the hat is embellished with handmade designs and dyes.

In the city of Cuenca, the shop assistant explains the manufacturing process and shows us some of the rarest, hand-designed hats: they are true works of art, finely crafted and carefully designed down to the last detail. A precious example of craftsmanship in which nature, indigenous tradition and culture intertwine to create an object strongly linked to the history of the Ecuadorian people and their land.

No Comments